Remembering Tropical Storm Allison 20 years later: A lesson in resiliency

In a region defined by hurricanes and severe weather, one storm stands out in its devastating impact on the Texas Medical Center and The University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth).

Tropical Storm Allison dropped more than 40 inches of rain on Houston in 2001, causing widespread flooding and severe consequences. McGovern Medical School at UTHealth and Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center were among the hardest-hit medical institutions.

“I didn’t know what the word resiliency meant then, but it’s been top of mind during the pandemic,” said Michael Blackburn, PhD, executive vice president and chief academic officer at UTHealth, who was a researcher in the biochemistry and molecular biology department at McGovern Medical School in 2001. “I see a lot of parallels in what this institution has been through this year and what we went through in Tropical Storm Allison. It was resiliency and people that got us through.”

The storm made landfall on June 4, 2001, and meandered up the Texas Gulf Coast. Similar to Hurricane Harvey, Allison receded back into the Gulf and recharged, bringing intense rainfall into an already saturated city. The heaviest rain days for the Texas Medical Center were from June 8 to June 10.

After three days of rain, the doors to McGovern’s loading dock caved under the pressure of 22 feet of water. The resulting tidal wave flooded the basement and first floor of the building, taking decades of research with it. At the time, animal care and associated research activities were located in the basement. More than 4,700 research animals in total were lost, along with filing cabinets of research findings and records. The gross anatomy lab and storage, as well as the university’s cyclotron facility – used to make radioisotopes for imaging – were also rendered inoperable.

The rising water burst into the basement of Memorial Hermann-TMC, short-circuiting key electrical components and disabling the hospital’s emergency backup power generator. More than 600 patients were safely evacuated in hot and damp conditions.

In rebuilding, UTHealth came back stronger, with larger and more advanced research space and strong protocols to prevent losses of the magnitude experienced from Allison. Lessons learned from the storm shaped how UTHealth evaluates building layout, construction, and maintenance.

In total, it was estimated that 10 million gallons of accumulated water filled the medical school basement. The storm caused $87 million in damage to the medical school’s building and its contents, as well as more than $7 million in costs associated with redeveloping lost research projects.

Cleanup efforts

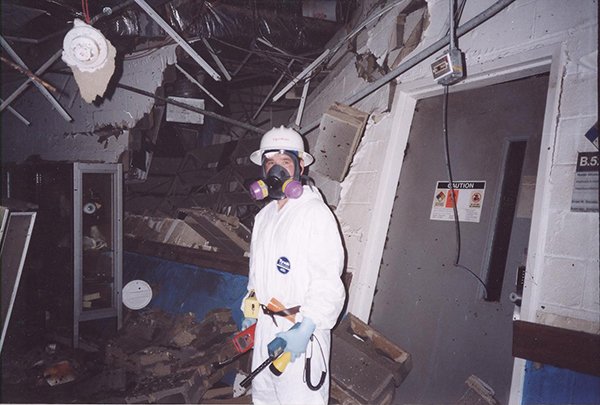

Several days after the flood, contractors were still on site pumping water out of the basement. Once the basement was clear of floodwater, breathing air within the space remained unsafe and was deemed “immediately dangerous to life or health.” Trained crews from Environmental, Health, and Safety wearing protective hazmat suits and respiratory protection were the first to survey the damage. Documents deemed irreplaceable were collected on a priority basis and placed in an area for a specialized process in an attempt to salvage them.

“The work was grueling,” said Bob Emery, DrPH, vice president for Safety, Health, Environment and Risk Management. “We were wearing fully encapsulating suits and respirators; it was dark and hot, and walls and ceilings had collapsed.”

Meanwhile, with no power in the building, researchers housed in upper floors of the building worked to save their frozen specimens by adding dry ice to freezers; teams pitched in to climb seven flights of stairs repeatedly to replenish the dry ice and keep samples viable until they could be moved to a different location.

Research and animal care

Mary Robinson, DVM, DACLAM, executive director of the Center for Laboratory Animal Medicine and Care and institutional attending veterinarian, was set to begin work at her first instructor-level position after completing her postgraduate work on June 12, two days after the rain stopped. She came to UTHealth from the postdoctoral program at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and started work a day late, with a backpack as her office. The animals she was hired to look after were lost in the flood.

“I had one year of experience in laboratory animal medicine and surgery, which didn’t prepare me for starting at an instructor-level position at a facility that was so recently devastated and trying to come to terms with what had to be done to rebuild,” she said.

All of the center’s offices were affected by the flooding.

“Once we were able to go down, it was dark and hot,” she said. “You couldn’t tell what anything was. You had to have a mental map in your head to be able to navigate it. There was devastation everywhere; walls were down, items toppled over, things were broken.”

In rebuilding, animal facilities were strategically placed on upper floors of buildings throughout campus.

“It was emotionally draining and physically draining trying to figure out how to forge ahead despite all that had happened,” Robinson said. “Although it was difficult to push aside emotions about what was lost, the experience taught me to be resilient and figure out answers when the answers aren’t apparent, and to work and collaborate with people from different departments. We all worked together, pulled together, and helped each other through the recovery, which took years.”

Among them was Blackburn’s lab, which lost all of its genetically engineered mice used in researching asthma and pulmonary fibrosis, a mysterious and progressive lung scarring condition. The research team banded together to see what other avenues it had before giving up.

“The questions and problems we were trying to solve were the most important things, and they survived the test of time, and in rebuilding, we were hungry,” Blackburn said. “We were scared, but hungry to do better and not let this beat us. I saw that same spirit throughout the entire medical school.”

Blackburn went on a nationwide journey to save his mice. Collaborators across the nation reached out when they heard what happened in Houston, but despite his efforts, the lab mice were unable to be recreated. Instead, new technologies filled in the gap and made the science stronger.

“My team came up with new ideas to answer the same questions,” he said. “Instead of just using mice, we branched out. We started using cell-based approaches instead of animal-based approaches. We started using informatics, and doing things that we wouldn’t have done otherwise. This event forced us to get out of the box we were in, and in the end made our science stronger. We received a $10 million program project grant for the institution based on the work we did coming out of Tropical Storm Allison.”

UTHealth was also able to expand its research footprint with the medical school expansion building, which opened in 2007, immediately adjacent to the existing medical school building.

“We owe that we have such a wonderful facility now to the fact that UTHealth leaders and the Texas Legislature said, ‘Never again will we put UT’s animals in the basement,’” Robinson said.

Patient evacuations at Memorial Hermann

In conditions that can only be described as miserable, UTHealth and Memorial Hermann health care workers banded together to take care of patients as the floodwaters knocked out electricity to the at-capacity hospital. About 600 patients were evacuated, including babies in the neonatal intensive care unit, burn victims, and trauma patients.

Richard Andrassy, MD, executive dean ad interim at McGovern Medical School, was chief of surgery in 2001. With a military background serving in the U.S. Air Force, he said the scene was as close to a war zone as he’s seen in the United States.

With no electricity or functioning emergency backup generators, life-sustaining machines like ventilators were inoperable. Pumps that dispensed medications stopped. Doctors and nurses worked to bag patients and hand-ventilated them until they could be transported. They took turns since the squeezing motion can be tiring on the hands.

“The problem’s solution sounds easy – transfer the patients – but first you had to find where to send them, and then you had to get them out of the hospital,” Andrassy said. “There was no elevator service. There was no lighting in the stairwells. It was humid, wet, dark, and hot. The problem was getting the patients down. It was really pretty miserable for everyone, including the patients, but the community banded together to help.”

Medical staff, residents, and students came in to help, some swimming across flooded streets to get there. Patrons of a nearby bodybuilding gym helped, too.

“These big guys who had been at the gym came over and strapped these gurneys to their back and carried patients down,” Andrassy said. “It was quite an effort. We all tried to pitch in and get up to the floors and help patients and and get equipment we needed. If it weren’t for some of these volunteers, it would have been really, really tough.”

Administrators with trucks were tasked with bringing in more people to help, while others coordinated transport and airplanes. Patients were flown to San Antonio and Dallas for care. One patient couldn’t be transported down the stairs, so volunteers broke a window, and brought the patient down using a crane.

Student learning and clinical activities

Once the floodwaters cleared, UTHealth officials began the long, arduous process of rebuilding.

“The storm caused a major interruption in clinical practice and clinical revenue,” said L. Maximilian Buja, MD, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, who was dean of McGovern Medical School at the time. “We made arrangements to get our clinical practice up and running again. It was a day-by-day situation, making incremental progress bringing these things back.”

The medical school building was without power for weeks, displacing 3,200 faculty, students, and staff.

At Memorial Hermann-TMC, 525 physicians and 800 residents were displaced from their usual practice sites as classes and clinical rotations were spread throughout the Texas Medical Center.

One of the key questions was how to get the gross anatomy lab back, which is a requirement for first-year medical students. Kurt Clark, manager of anatomical services at McGovern Medical School, said that while UTHealth worked to set up a temporary gross anatomy lab in its Operations Center Building (OCB), Baylor College of Medicine allowed UTHealth students to use its facilities.

“The biggest obstacle in outfitting OCB to be the anatomy lab was that type of space requires what we call 100% outside air, where the air is constantly circulating in the space,” said Gerard Marchand, director of real estate, space, and facilities management at UTHealth, who was over maintenance at the medical school in 2001. “We had to buy new air conditioning equipment that didn’t exist before and install it. We also put down this specialized epoxy flooring. It was a big deal. Contractors worked second and third shifts to get the job done as quickly as possible. “

While contractors worked to establish temporary power in the building, institutions across the TMC offered up what space they could to help. Students and research groups met in coffee shops and restaurants. Andrassy said his home became the headquarters for the Department of Surgery until space was found. Elective procedures were delayed, but the department was able to schedule other procedures at Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital, which was unaffected by the flood.

UTHealth leaders were thoughtful in their rebuilding of the basement, and in the construction of the medical school expansion building, which was built on the footprint of the old John Freeman Building. In the end, the university was able to upgrade its facilities for animal care and gross anatomy, and add a clinical skills center.

Lessons learned and safeguards put in place

Following Tropical Storm Allison, UTHealth allocated more than $20 million to add flood safeguards to the McGovern Medical School and expansion buildings. The university has kept a focus on safeguarding its campus by completing annual flood projects at various buildings on campus. These projects include relocating electrical systems from ground floors, adding retaining walls, weatherizing windows, and other projects.

These efforts have paid off. In 2017, property damages were minimal during Hurricane Harvey. During that storm, the university incurred $3 million in damages across the entire campus, compared to the $87 million during Allison at the medical school alone almost two decades before.

The medical school now has three layers of protection including an outer berm with water collection pits and pumps, a hydrostatic wall that provides protection 1 foot above the 500-year flood level, and 23 outer and inner flood doors in the basement and ground level of the building.

The gross anatomy lab and clinical skills center are situated behind an additional layer of submarine-like doors, which are tested each year to ensure they are in prime condition should a flooding event occur. The manual doors are designed to be closed by one person within five minutes. Similar doors are also installed at UTHealth School of Public Health and the Jesse Jones Library Building.

“The installation of the flood doors prevented substantial losses from subsequent storms,” said Mark Ferguson, who retired as the director of maintenance, operations and contact services at UTHealth in February 2021. “We go through an annual testing and training session to make sure everything is working properly. The doors have two seals, one inside and one outside. We replace the seals on a manufacturer-recommended schedule.”

Tropical Storm Allison was a pivotal point in the history of McGovern Medical School and UTHealth, and the university was able to emerge from the tragedy with stronger bonds.

“We have always been a great school, but that event brought out the best in people. There are countless stories about dedication and commitment,” Blackburn said. “Leadership of our institution came through with the dollars, resources, and the forgiveness of time to allow us to recover. I see that resilient spirit during this pandemic as well. It’s become a part of the fabric that makes UTHealth unique.”

Be Prepared

It’s officially hurricane season. The UTHealth community is encouraged to review their department call trees, and to have a printed copy of both the university’s Emergency Management Plan and call trees should the need arise.

Tips for hurricane preparedness at home and in the workplace can be found on the UTHealth intranet.